MALNUTRITION

MALNUTRITION

Malnutrition

Malnutrition includes both under nutrition - acute

malnutrition (i.e. wasting and/or nutritional oedema), chronic malnutrition

(i.e. stunting), micronutrient malnutrition and inter-uterine growth

restriction (i.e. poor nutrition in the womb) -and over nutrition (overweight

and obesity.

Acute malnutrition or wasting (and / or oedema) occurs when

an individual suffers from current, severe nutritional restrictions, a recent

bout of illness, inappropriate childcare practices or, more often, a

combination of these factors. It is characterized by extreme weight loss,

resulting in low weight for height, and/or bilateral oedema,

and, in its severe form, can lead to death. Acute malnutrition

reduces resistance to disease and impairs a whole range of bodily functions.

Acute malnutrition may affect infants, children and adults. It is more commonly

a problem in children under-five and pregnant women,

but nonetheless this varies and must be properly assessed in each context.

Levels of acute malnutrition tend to be highest in children from 12 to 36

months of age when changes occur in the child’s life such as rapid weaning due

to the expected birth of a younger sibling or a shift from active breastfeeding

to eating from a family plate, which may increase vulnerability.

The most visible consequences of acute malnutrition are weight loss

(resulting in moderate or severe wasting) and/ or nutritional oedema (i.e.

bilateral swelling of the lower limbs, upper limbs and, in more advanced cases,

the face). Acute malnutrition is divided

into two main categories of public health significance: severe acute malnutrition (SAM) and moderate acute malnutrition (MAM). MAM is characterised by moderate

wasting. SAM is characterised by severe wasting and/or nutritional oedema.

The term global acute malnutrition

(GAM) includes both SAM and MAM. Mild acute malnutrition also has consequences

but is not widely used for assessment or programming purposes.

Acute

malnutrition increases an individual’s risk of dying because it compromises

immunity and impairs a whole range of bodily functions. When food intake or utilisation (e.g.

due to illness) is reduced, the body adapts by breaking down fat and muscle

reserves to maintain essential functions, leading to wasting. The body also

adapts by decreasing the activity of organs, cells and tissues, which increases

vulnerability to disease and mortality. For reasons not completely understood,

in some cases, these changes manifest as nutritional oedema.

A ‘vicious cycle’ of disease and malnutrition is often observed once these adaptations

commence.

Moderate Acute Malnutrition (MAM)

The burden of MAM (wasting) globally is

considerable. Around 41 million children are moderately wasted worldwide and

the management of MAM is finally becoming a public health priority, given this

increase in mortality and the context of accelerated action towards achievement

of Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) 3 and 4. Children with MAM have a

greater risk of dying because of their increased vulnerability to infections as

well as the risk of developing SAM, which is immediately life threatening.

Some children with MAM will recover spontaneously

without any specific external intervention; however the proportion that will

spontaneously recover and underlying reasons are not well documented.

8.2

Severe Acute Malnutrition (SAM)

Acute

malnutrition is distinguished by its clinical characteristics of wasting and /

or bilateral pitting oedema

- Marasmus – severe wasting presenting as

both moderate and severe acute malnutrition

- Kwashiorkor

–

bloated appearance due to water accumulation (nutritional bilateral

pitting oedema)

- Marasmic kwashiorkor- is a condition which combines

both manifestations.

It

usually develops rapidly as a result of protein deficiency, or more commonly,

it is precipitated by an illness such as measles or other infections. It occurs

mainly in older infants and young children aged 1 to 3 years.

Clinical signs

- Poor growth characterized by loss

of weight and growth failure (60 to 80% weight for age).

- Oedema- accumulation of fluids in

tissues causing swelling

- Wasting of muscles

- Mental changes characterized by

apathy, misery, irritability and sadness.

- Hair changes- the hair becomes

coarse, lack of luster, brownish, sparse and easily pulled out.

- Anaemia due to lack of protein to

synthesize blood cells is worsened by iron deficiency, malaria and worm

infestation.

- Skin changes/lesions- dark

pigmentation in areas of friction i.e. patches like sun burns.

- Diarrhoea

- Moon face-cheeks appear swollen

with fatty tissues or fluids.

- Poor appetite/ anorexia

- Hepatomegaly (enlarged fatty

liver).

8.2.2 Marasmus (Chronic PEM)

Occurs commonly in children from 6 to 18 months of age. The

deficiency is primarily due to lack of energy especially in starvation and is

worsened by infections and parasitic diseases.

Clinical signs

- Growth failure (weight for age

less than 60%)

- Severe muscle wasting

- Alert though with deep sunken eyes

- Good appetite (violent suckling of

hands)

- The face is wrinkled and drawn in

( look like an old man)

- Diarrhoea

- Dehydration.

It

is a mixed form of PEM, and manifests as oedema occurring in children who may

or may not have other signs of kwashiorkor. It reflects as a deficiency of both

energy and protein.

8.2.3.1 Clinical signs

- Flaky paint dermatitis

- Mental changes

- Hepatomegaly

- Diarrhoea

- Dehydration

- Oedema

Prevention of PEM

PEM can be prevented by:

a.

Giving

children adequate food that is energy and micronutrient dense.

b.

Exclusively

breastfeeding infants for the first six months and then introduction of

nutritious complementary foods starting at six months with continued

breastfeeding up to two years and beyond.

c.

Preventing

or treating infectious diseases promptly since they increase nutrient needs.

d.

Deworming

children to eradicate worm infestations which contribute to low nutrient

utilization.

e.

Enhancing

proper sanitation when handling, preparing and feeding children to prevent

contamination. The water used to prepare feeds should be clean.

f.

Promoting

good maternal nutrition since it contributes to the health outcome of the baby.

Poor maternal nutritional status leads to delivering preterm and low birth

weight babies who are at risk of developing PEM.

g.

Promoting

health education especially among the care givers of children.

Micronutrient Deficiencies

Micronutrients are minerals and vitamins that are needed in

tiny quantities (and are therefore known as micronutrients). Micronutrient deficiencies account for roughly 11%

of the under-five death burden each year.It is now recognised that poor growth

in under-fives results not only from a deficiency of protein and energy but

also from an inadequate intake of vital minerals (e.g., zinc), vitamins, and

essential fatty acids.

Vitamins are either water-soluble

(e.g. the B vitamins and vitamin C) or fat-soluble (e.g. vitamins A, D, E and

K). Essential minerals include iron, iodine, calcium, zinc, and selenium

Key

micronutrient deficiencies

· Iron deficiency leads to iron

deficiency anaemia

· Vitamin C deficiency leads to scurvy

·

Vitamin

A deficiency leads to xerophthalmia

·

NiacinorVitamin B3 deficiency leads

topellagra

· Iodine deficiency leads to goitre and

cretinism (in infants born to iodine deficient mothers)

· Thiamin or B1 deficiency leads to

beriberi

· Riboflavin

deficiency leads to ariboflavinosis

· Vitamin D deficiency leads to rickets

The main cause of micronutrient

malnutrition is usually an inadequate dietary intake of vitamins and/or

minerals.

Causes of Malnutrition

UNICEF’S conceptual framework on the causes of malnutrition:

a.

Immediate causes: Inadequate food intake and presence

of disease

b.

Underlying causes: inadequate household food security;

inadequate maternal and child care; inadequate health services and unhealthy

environment

c.

Basic causes: resources and control; human;

economic and organizational; political and ideological superstructure;

potential resources; technology;

environment; people

Conceptual Framework of

Malnutrition

The basic causes of malnutrition are greatly influenced by:

- Political situations and economic

systems that determine how resources are distributed

- Legal factors that determine how

far the rights of women and girls are protected by law

- Cultural factors i.e. the ideologies and policies governing

social sectors

To address basic causes of malnutrition, greater and better

targeted resources and better collaboration are needed between sections of

national governments and donors. United Nations Agencies, non-governmental

organizations and investors. Above all, the poor themselves must be a major

part of the process.

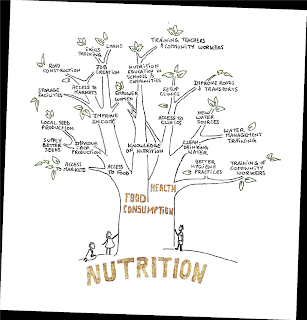

Solution Tree

To address the problem of malnutrition, a multi-sectoral approach is used. Many sectors work together to address the different causes.

The

preparation of a solution tree will present “Reduction of malnutrition” as a

common objective for an integrated approach addressing the various causes of

malnutrition, bringing together different technical departments within an

organization, or highlighting potential partnerships between organizations with

complementary expertise. A health agency providing nutrition treatment, for

example, could partner with a food security agency that will assist patients’

families in diversifying their food production, income sources and food

consumption, thus preventing relapses. Not only does the use of nutrition as a

common objective facilitate the identification of cross-sectoral linkages, it

also carries meaning.

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment